customizing and extending R code

By customizable, we mean that we can control the behaviour of a function via its parameters, and specifically, that we can pass a function in to the function that is used to do a particular step in that function. Below we discuss the scheduler parameter which takes a function that computes the schedule. By being able to provide a function, we don’t have to define a new class and a new method and then create an instance of that new class to get our new method invoked. The function is more direct, dynamic and ephemeral. It is in effect for this function call.

By extensible, we are referring to infrastructure and more specifically extensibility via class extension/subclassing/interfaces in the Object Oriented Programming (OOP) world. So we can extend the existing code base without modifying it by defining one or more new classes (typically derived from an existing class) and then providing methods for this new class. Then we create a new instance of our new class and pass it into the existing system and the new methods get invoked appropriately.

Application

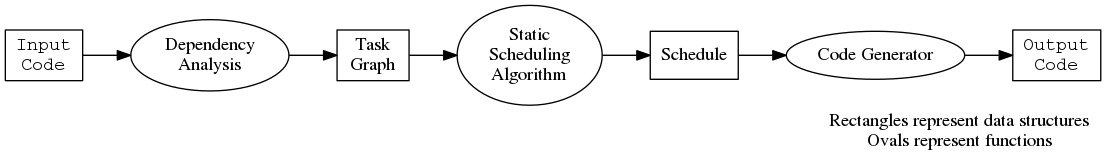

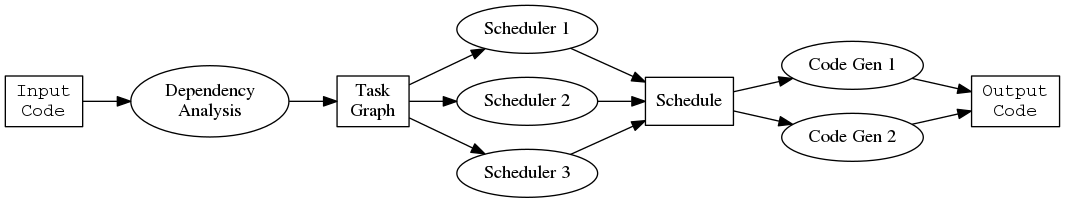

We’ll explore these concepts in the context of a concrete example. The software described below transforms regular R code into a version that uses task parallelism, which means that different code blocks execute simultaneously. This graph illustrates the steps:

The package contains a function task_parallel implementing the above

steps, so users write:

newcode = task_parallel(oldcode)

We discuss how to design this function task_parallel to be flexibile and

customizable with respect to the four objects in the diagram:

- input code

- task graph

- schedule

- output code

and with respect to the three functions in the diagram:

- dependency analysis

- scheduling algorithm

- code generator

This document demonstrates incremental steps to make functions more extensible and customizable.

Simple

Here’s the simplest way to implement task_parallel:

task_parallel = function(code)

{

tg = task_graph(code)

sc = scheduler(tg)

code_generator(sc)

}

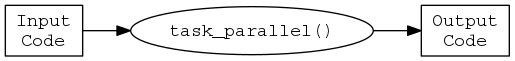

This has the advantage of convenience for the user, because it implies the following mental model.

task_parallel() is a black box, completely abstracted away. The user only

controls what code they pass in. Sometimes this level of abstraction is

entirely appropriate, as we don’t want to force users to have to understand

all aspects of the implementation. Indeed, the entire purpose of a function

is to provide a convenient abstraction. The problem with this

implementation is that it fixes the scheduling algorithm and code generator

so that the user has no control over the behavior of the task_parallel

function.

As we make the function customizable and extensible we would like to always

keep this simple behavior that allows users to write autoparallel(code).

It’s convenient, it’s the most common use case, and it includes users who don’t

care about understanding any of the underlying mental models, they just

want the end result.

Multiple Inputs

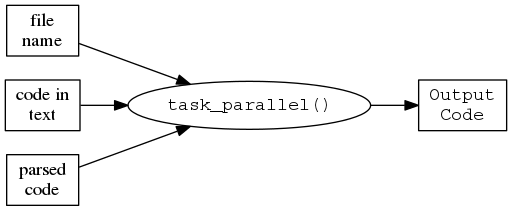

The user may prefer to pass in different types of input to task_parallel.

For example, they may have the name of a file containing code,

a bunch of code in a character vector,

or maybe a language object produced by R’s parse() function.

We can keep the current definition for task_parallel and achieve this

behavior by making task_graph a generic function. This means task_graph

will dispatch on the class of the input code. This is a better choice

than making task_parallel a generic function, because then task_graph

becomes flexible and propagates this flexibility through to the calling

function task_parallel. In S3 our code might look like the following:

task_graph = function(code, ...)

{

UseMethod("task_graph")

}

task_graph.character = function(code, ...)

{

# ... Disambiguate file names from a character vector of unparsed code

TODO: use of I() here

task_graph(parse(filename))

}

task_graph.expression = function(code, ...)

{

# The actual work of building a task graph

}

Passing Arguments Through

The scheduler happens to be the most complex step in the process, and we

would like to provide a way for users to easily control these parameters.

R’s ellipses ... provide a mechanism for this.

Note that it really only makes sense to use this with a single function.

task_parallel = function(code, ...)

{

tg = task_graph(code)

sc = scheduler(tg, ...)

code_generator(sc)

}

Now if a user wants to specify another argument to the scheduling step, say

maxworkers = 3L to create a schedule with three workers they can easily

do this:

newcode = task_parallel(code, maxworkers = 3L)

We could take this further and pass in further arguments in the form of a

list from task_parallel in to the other steps task_graph and

code_generator. We are not doing this at the moment for two reasons. First,

we don’t currently see a need for specifying many arguments for these two

functions. Second, it’s easy to add later without breaking anything.

Customizability

In the original computational model the scheduling algorithm and the code generation are meant to be modular. Users can customize the system by supplying their own functions that implement scheduling or code generation.

The code becomes:

task_parallel = function(code, scheduler = default_scheduler, ...

code_generator = default_code_generator)

{

tg = task_graph(code)

sc = scheduler(tg, ...)

code_generator(sc)

}

Now users can define and use their own scheduling algorithms, for example

genetic_scheduler that uses a genetic algorithm.

newcode = task_parallel(code, genetic_scheduler)

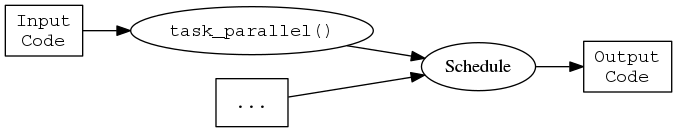

Suppose the user wants to modify some part of the pipeline. If the user has

a schedule in hand then they can directly call the code generator, and

there’s no need to use task_parallel. But they may want to modify the

task graph and pass this directly in. R evaluates arguments lazily, so we

can allow users to pass in a task graph by lifting the first line in the

body of the function into a default parameter:

task_parallel = function(code, taskgraph = task_graph(code), scheduler = default_scheduler,

..., code_generator = default_code_generator)

{

sc = scheduler(taskgraph, ...)

code_generator(sc)

}

We could even lift several lines into default parameters, provided that we avoid circular references.

Extensibility

Some schedulers must be tied to their code generators. We want the runtime to figure out what the most appropriate code generator is and use that. This is where the extensibility through object oriented programming comes in. We change the package code as follows:

generate_code = function(schedule, ...)

{

UseMethod("generate_code")

}

generate_code.default = function(schedule, ...)

{

# ... more code here ...

}

At this point two of the three steps in the model use methods. We may as well be consistent and make the scheduling step a method, even though we don’t expect to dispatch on many different classes of task graphs.

schedule = function(taskgraph, maxworkers = 2L, ...)

{

UseMethod("schedule")

}

schedule.default = function(taskgraph, maxworkers, ...)

{

# ... more code here ...

class(result) = "Schedule"

result

}

The primary function becomes:

task_parallel = function(code, taskgraph = task_graph(code),

scheduler = schedule, ..., code_generator = generate_code)

{

sc = scheduler(tg, ...)

code_generator(sc)

}

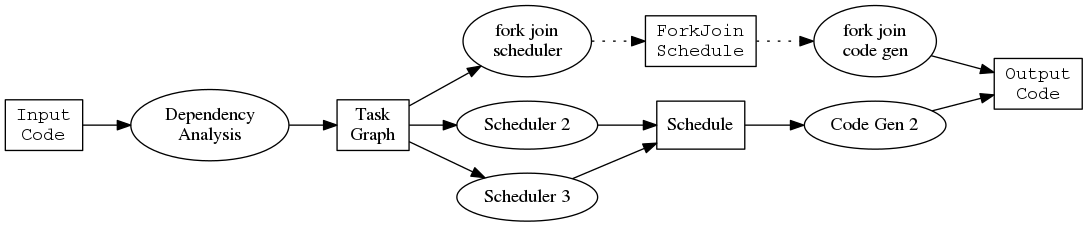

Now we can extend the system through object oriented programming. For

example, fork_join_schedule is a scheduling algorithm that returns a more

specialized schedule that supports a particular type of code generator.

Then we don’t want to use the default_code_generator. By using a generic

function the user OR the package author can define a scheduling

algorithm with an associated implementation as follows:

fork_join_schedule = function(taskgraph, maxworkers = 2L, ...)

{

# ... more code here ...

class(result) = c("ForkJoinSchedule", "Schedule")

result

}

generate_code.ForkJoinSchedule = function(schedule, ...)

{

# ... more code here ...

}

We can call this new code as follows:

task_parallel(code, scheduler = fork_join_schedule)

fork_join_schedule creates an object of class ForkJoinSchedule, and

generate_code will dispatch to the specialized method. These objects

become implicitly tied together which is what we wanted.

Summary

We started with a function task_parallel that could only be called in one

simple way:

task_parallel(code).

We preserved this desirable simple behavior and extended it so that users can do any of the following:

task_parallel("some_script.R")methods for different classes of the first argument.task_parallel(taskgraph = tg)skips the setup part of the function in case the user has already done that or they have a special task graph to use.task_parallel(code, schedule = my_scheduler, code_generator = my_code_generator)allows users to customize the steps in the process by passing in their own functions to perform them.task_parallel(code, schedule = fork_join_schedule)dispatches on the class allowing users to extend the system through defining their own classes.

This style of code accommodates three increasingly sophisticated classes of users:

- Users who just want to treat it as a black box

- Users who understand the model and would like to experiment by passing in new functions

- Users who would like to extend and build upon the system by writing methods and using object oriented programming techniques

The final version of the code supports all of these use cases simultaneously. Further, we don’t force users to do it in any particular way. This is nice as each usage style has its merits.

Appendix - Final code

# Different inputs

#------------------------------------------------------------

task_graph = function(code, ...)

{

UseMethod("task_graph")

}

task_graph.character = function(code, ...)

{

# ... Disambiguate file names from a character vector

task_graph(parse(filename))

}

task_graph.expression = function(code, ...)

{

# The actual work of building a task graph

}

# Allows extension through intermediate objects

#------------------------------------------------------------

generate_code = function(schedule, ...)

{

UseMethod("generate_code")

}

generate_code.default = function(schedule, ...)

{

# ... more code here ...

}

schedule = function(taskgraph, maxworkers = 2L, ...)

{

UseMethod("schedule")

}

schedule.default = function(taskgraph, maxworkers, ...)

{

# ... more code here ...

class(result) = "Schedule"

result

}

# Final user facing function

#------------------------------------------------------------

task_parallel = function(code, taskgraph = task_graph(code),

scheduler = schedule, ..., code_generator = generate_code)

{

sc = scheduler(tg, ...)

code_generator(sc)

}